Jun 6 2016

Planting seeds — The Simplest, Most Powerful Thing a Child Can Learn

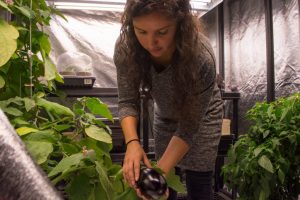

“If they plant it, they’ll be more eager to eat it,” says L’Ecole Abbey-Landry teacher François LeBlanc of his students. “At basis we need to eat better.” If there is one reason why teacher François LeBlanc got involved in establishing a greenhouse project for the school in Memramcook it’s that.

But it turns out to be more than that. “I’m more just trying to find different ways to teach. I like to tinker with things and I know kids do, too.” If this sounds like a teacher who likes to do things with his students, you’re probably right. And if you think he’s getting as much as the kids out of the program you’d be right about that, too. We talked to both François and Véronic Cormier, the coordinator of the program, and throughout it was obvious they were on the journey, too. The greenhouse, now that it’s up and running, has got their imaginations fired up with all the possibilities for education and for the community.

The possibilities

In the hour or so we talked they spoke of the possibility of feeding the school and feeding perhaps the nearby seniors complex, as well as having a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program. They hope to find their place in the agricultural scene of the area. “One of the challenges is to find our niche,” says François, “maybe herbs or microgreens. No one here is doing microgreens.” They talked about having one crop they specialize in to pay the bills, as well as doing experiments with “weird” vegetables.

While not an expert, François is an avid gardener. “I’m self-taught. I do it on the weekend and at night, that’s when I do it. I try to stop that and get my school stuff done.” Véronic is also self-taught but is also studying nutrition at a school in Moncton.

The educational value of the greenhouse cannot be underestimated but there are challenges there, too. “It’s tough because you do have to follow a curriculum and we’re working closely with another school,” he says. “But I think the school vision with the principal we have now (Pierre Roy) is to have project-based learning and real-life things. He loves the whole entrepreneurship thing, getting kids involved.”

The business of greenhouses

The greenhouse is industrial sized at 33’ x 75’ and has room for whole classes to come in. It was donated by the local golf club who didn’t need it anymore. It was erected by a contractor.

The first day we were there seeds had just been planted but on the second visit the place seemed filled with bedding plants and apparently they had already had at least one sale.

On the day we visited there were seniors from nearby Le Manoir du Mascaret were stocking up on bedding plants.

The children we met that day were Grade 6 students Janelle Bourque and Danika LeBlanc and they had the manner of experienced sales staff. When asked what about the project had impressed them most it was, “M. François trusts us with the money.”

Both girls gardened at home, Janelle for a few years, but this was Danika’s first. She said it was easy now that she had already done it. And she says she loves it. She’s not the only one. “A couple of parents sent letters to the principal,” says François, “and said what we’re doing is helping their kids. Before they didn’t want to go to school. Now they’re loving the whole thing.”

One of the seniors there, Juliette Landry, was a retired Abbey-Landry teacher who said, “Every school should have a greenhouse.” Véronic thinks even bigger than that. “I would love to have another greenhouse and have one for full production and one for education.”

A community greenhouse

But the greenhouse is not just for the school. François and Véronic continually point out the benefits for the community as a place to gather and do gardening and for improving the health of people in the area.

Robert Bourgeois, owner of Belliveau Orchard, also sees the value of the project for the community. He is one of the business people and farmers consulted about how to make the greenhouse succeed. While he doesn’t think it could succeed as a full-blown, profit making business, he does believe in the project and its value to the school, its students and the community. “For the kids to have a hands-on experience to know where their food is coming from is worth something,” he says.

He also says they might think about forming a co-op “so people like me could could invest in it a bit, say, a thousand dollars a year” and with government incentives they could interest others. “It would help the community.”

François says there is still so much work to be done and so much that could be done. “We’re looking to do something for the community. It would be nice for people to jump on and give a hand.”

Jun 6 2016

Elaine Mandrona — Back to the Land Redux

Despite her misgivings, I decided to include Elaine Mandrona in this first issue of our Food Movement Beat because so many of the themes of her coming to New Brunswick echo those of many of the people we talked to in the last year, especially the young farmers.

She first came to New Brunswick from Connecticut via Wisconsin in the early seventies when she and her partner at the time visited expat friends who said this was the place to start a new life away from everything that was wrong with the world: war, social inequality, urban sprawl, crime, degradation of the environment.

New Brunswick was beautiful and pastoral, the people friendly and welcoming and the land was cheap. Really cheap. They had found a haven.

“And we believed change was imminent. We didn’t know it was still 45 years away,” she says.

Back to the land — Corn Hill

They first settled in the Corn Hill area. Elaine and her partner had a tough year of it when winter came. “We moved into a wreck of a house that should have been knocked down,” she says. “I don’t know why we thought a cook stove could keep us warm over the winter in a cold and drafty farmhouse.” A neighbor rescued them by giving them an old wood heater.

The idea that many of these young people had was they would go back to the very basics of life, back to the land, and live without the conveniences they believed were at the heart of all the problems they left behind. Inspired by authors such as Helen and Scott Nearing and their book Living the Good Life, they engaged rural life in New Brunswick.

Of course, no book truly prepares anyone for reality and the hardships they endured are sometimes hard to listen to. Their neigbhours were friendly and helpful, but “I think they thought we were nuts to want to live without electricity when they had just got it in the fifties,” she says.

Back to the land — Cedar Camp

That relationship broke down and she started a new one and a new idea of an intentional community in Cedar Camp in the Waterford area not far from what is now Poley Mountain. Five hundred acres cost $40,000 then and the idea was that each person would build their own house and work the land together.

The first winter was a frigid nightmare again. “We lived in a cabin made from scrap lumber and tea box lids. We burned alders for heat.” The next summer Elaine built her house by a brook but her partner moved in, too.

“I built my own hexagonal tiny house, ten feet on a side. As a woman it was important for me to learn some simple carpentry skills and do that. My partner and I lived there off the grid for 10 years using micro hydro and solar panels. We ran lights, a radio and a small refrigerator. I figure that I earned a lot of green footprint credits living that way.”

Then the others in the community could not get enough money to make the community work so Elaine and her partner took over the farm.

They tried a market garden but there was no farmers market back then and organic produce was not valued in rural New Brunswick. The closest thing to a venue was selling off the back of trucks every Wednesday at the livestock auction in Sussex.

Eventually, the living off the land idea gave way to other ideas about how to earn a living and Elaine went into business for herself. “Being self-employed gave me a lot of satisfaction and independence. I ran my own stained glass studio and craft shop, Glass Alley (in Sussex), for 18 years and later became a massage therapist and nutritional consultant. I’ve been practising massage for 25 years now, soon to retire.”

Back to the land — Moncton

“Archie and I moved to Moncton in 2005 to start a different life, one in the city and close to our cottage in Cocagne,” she says. “We have a big yard and I felt bad that I was not growing any food.”

That desire to grow food again manifested in a couple of garden boxes that grew enough food to encourage her to build a few more. The more food she grew the more boxes she wanted. Starting on such a small scale without the desperation of having to make it pay or store it for winter made it more enjoyable. She also wanted to share the experience and invited people. A couple of young women took her up on it.

“Then I took a Community Food Mentor program and it opened my eyes to all that was going on in the area around food. The program also encouraged me to come up with my own program that could expand food capacity in my community. Now I have the City Farming Adventures group and am running an intergenerational and multicultural garden project with seniors in partnership with the Moncton Boys and Girls Club.”

There is no talk of a market garden, though. She’s in a different place now. “I don’t want to sell food. I just want to grow food with other people, especially children because they love it so much. People are coming back to the land. They’re realizing how important it is to connect with their food and how it is grown.”

She says they’re coming back to the land. “It’s just 45 years later.”

By Archie Nadon • farming, First Issue, food movement, food security, gardening